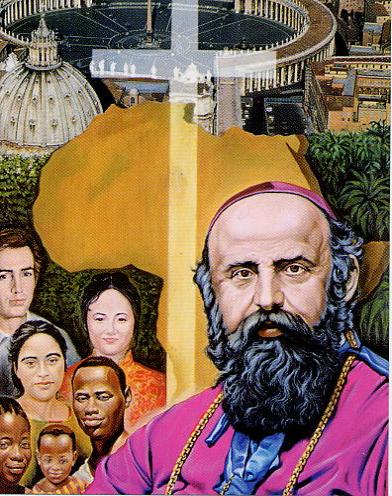

The Comboni Missionaries are an international missionary institute of priests and brothers, founded in 1867 by St. Daniel Comboni. Their sole purpose is to evangelize peoples where the truth of Jesus Christ has not yet been proclaimed or where it needs to be consolidated. They proclaim and announce the Gospel and collaborate in the development of peoples.

The Institute achieves its goal by sending its members where missionary activity is needed, in accordance with the charism of the Founder, fostering the missionary awareness of the People of God, promoting missionary vocations, and forming them for the mission.

In accordance with the inspiration of the Founder, the Institute is composed of priests and brothers. This particular feature more fully realizes the ecclesial character of the Institute and makes its activity and complementarity of services more fruitful.

Small cenacle of apostles

After trying to involve various institutes in the realization of his “Plan,” Daniel Comboni found himself obliged to found the “Institute for the Missions of Africa” in Verona on June 1, 1867: a small group of priests and brothers of various nationalities, united by an oath of belonging and fidelity to the mission.

With the death of Daniel Comboni (1881), a certain confusion arose among the cardinals and bishops interested in his mission. On the other hand, his missionaries and religious, both those in Italy and those in Egypt and Sudan, were able to face this tragic moment with great determination. However, in the early years, they were shaken by turmoil and suddenly subjected to a severe test. As early as 1882, Sudanese troops led by Mohamed Ahmed, who proclaimed himself “the Mahdi” (meaning “the well-guided one,” a descendant of Muhammad), ransacked the missions, took all the missionaries prisoner, and forced them to walk barefoot for weeks and months across the scorching desert sand.

Comboni's first successor, Bishop Francisco Sogaro, devoted himself to securing his release, but this was only achieved in 1898. Meanwhile, in Italy, consideration was given to strengthening ties between the missionaries and between them and their superiors, in order to provide greater stability and ensure the effectiveness of missionary work. For this reason, in 1885, the Institute became a religious congregation.

The new missionaries, thus reinforced and consolidated, began to return to the mission. They went first to Egypt (1887) and then to Sudan (1900), where they had to rebuild all the missions destroyed by the followers of the Mahdi. But not content with that, they advanced southward.

In the heart of Africa

The new missionaries were called “Sons of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.” Comboni, a great devotee of the Sacred Heart, had spread its spirituality and various devotions. One of these missionaries, Monsignor Antonio Roveggio, Comboni's second successor, went so far south in Sudan that he almost reached Uganda. But fevers interrupted his life: he died in 1902, at the age of only 43.

It was up to his successor to penetrate the heart of Africa, among the powerful tribes of the Denka, the tall Shilluk, and the hardworking Bari. There were many difficulties: in a region of Southern Sudan called Bahrel-Gazal, five missionaries died in one year, and others had to spend long periods in Cairo or Italy to recover their health. Bishop Francisco Javier Geyer, Comboni's third successor, was not discouraged by this; on the contrary, he went even further south and, in 1910, he met a group of missionaries in Uganda.

Progress and difficulties of the Institute

Although, according to Comboni's wish, the members were of various nationalities, there were two larger groups: the Italians and the Austro-Germans. Due to problems related to that historical moment, at the General Assembly (or Chapter) of 1919, it was decided that the two groups should have a certain degree of autonomy. However, after hearing the opinion of the Superior General, Fr. Pablo Meroni, the Holy See decided in 1923 to divide the Institute into two missionary congregations. Their reunification took place in 1979. This was possible because both groups had preserved their missionary identity and, above all, the memory of Comboni. Fr. Paolo Meroni deserves credit for having introduced, in 1927, the process of beatification of Daniel Comboni, the Founder.

Expansion and internationality

Father Antonio Vignato, one of the pioneers of the missions in Sudan, will be the one to open up to other nations in Europe and across the Atlantic. Elected Superior General in 1937, he is aware of the needs of the missions in Africa, which at the time were under British rule, and in 1938 he opens a house in England. Once established in that Atlantic country, he took his missionaries to the United States (1939): he needed more English-speaking personnel and also financial assistance. German-speaking brothers arrived in Peru in 1938. Due to identical needs in the missions of Mozambique, where Portuguese is spoken, a house was opened in northern Portugal (1947). It was then up to Fr. Antonio Todesco, Superior General from 1947 to 1959, to study the needs of the missions on the American Pacific coast, in Baja California, Mexico, in January 1948.

But who could stop the Comboni missionaries? In 1952, it was Brazil's turn: first in the north, the poorest part of the country, and later in the slums of the big cities in the south.

Having learned of the vigorous expansion of the Comboni missionaries, the Holy See, through Propaganda Fide, asked them to also take responsibility for a territory in Ecuador, in Esmeraldas. The first missionaries arrived there in 1954 and, as some of them had already been in Africa, they felt at ease among these black people, called “morenos.” The people from Spain (1954) provided invaluable help in these countries because of the language.

Growing towards the East

Despite expanding across the Atlantic and to the shores of the Pacific, Africa was never neglected. The first missions entrusted to Comboni were Egypt, Sudan, and Uganda, the latter of which he was unable to reach despite his ardent desire.

His successors would arrive in 1910. Later, in order, would come: Ethiopia (1939), Eritrea (1942), and Mozambique (1947).

In the 1960s, French-speaking territories were also added: Democratic Republic of Congo - “former Zaire” (1963), Togo (1964), Burundi (1964), Central African Republic (1964).

The German brothers had already been in South Africa since 1923.

In the 1970s, new openings included Kenya, Ghana, Malawi, Chad, and Benin in Africa, and Costa Rica in Latin America.

In recent years, the presence in Central America (Guatemala and El Salvador) has been consolidated and, driven by the signs of the times, also in the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Macau, in Asia and the Middle East.